Vetiver and Turpentine

An Island Is a World

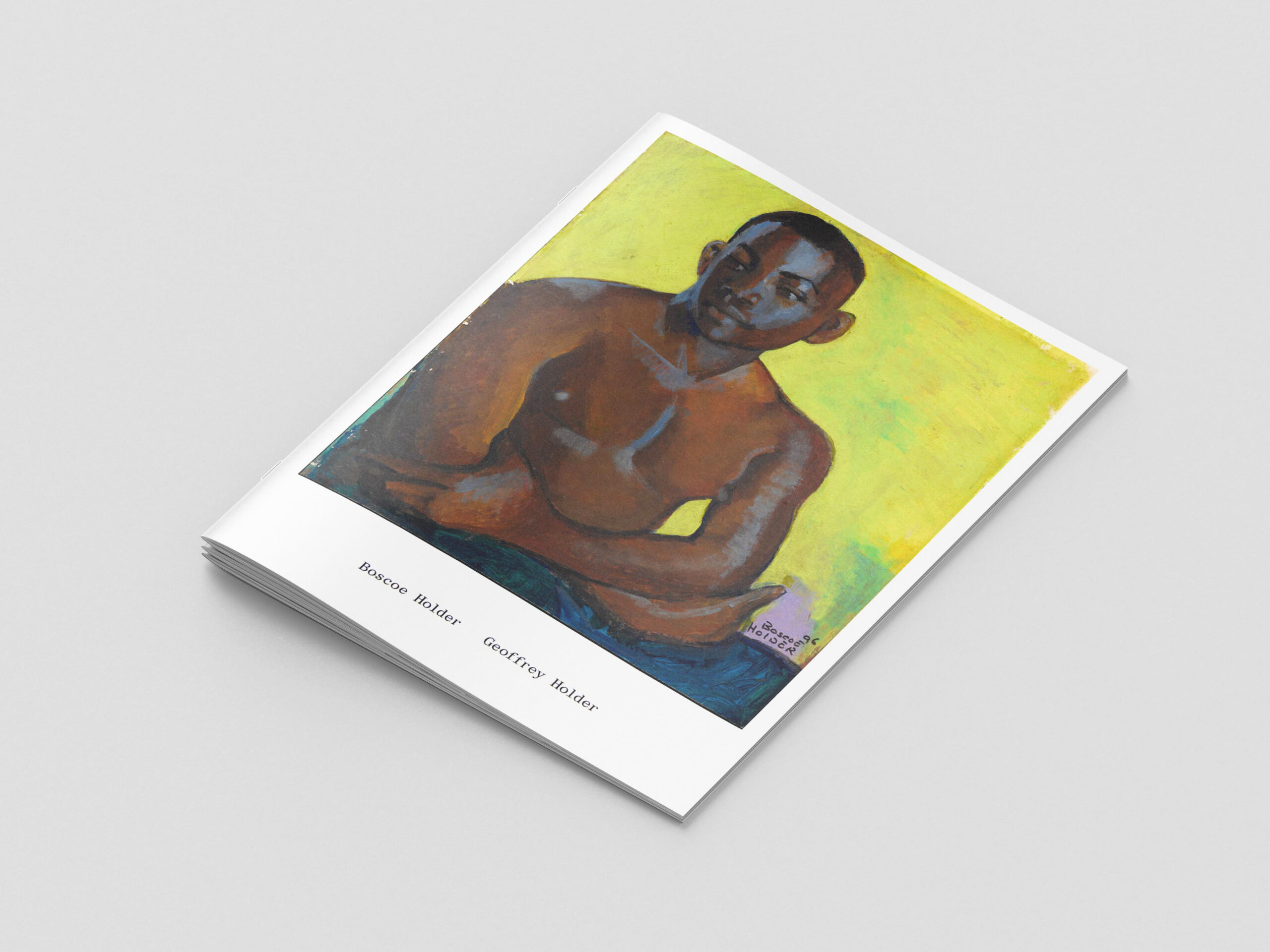

Consider this: two black boys living their most audacious version of a freedom dream in Trinidad, a small place with the world shoved into all its corners. And the boys, who live in a small house, are surrounded by love and art and music shoved into all its corners. In this house, at 78 Richmond Street, there is a room with a hard bed and pictures on the wall and a piano in the corner. And it is close enough, if you pay attention, for the smell of the Caribbean Sea to waft into its rooms. And the smell of the sea mixes with the heady musk of vetiver and turpentine. And their bodies are as African as that mango tree is Indian, as their manners are French, as their deference to power is from the British, who have named the streets of this small island town for the ugliest of warlords and the cruellest of governors. The father is a stoic and meticulous, a salesman whose father came from Barbados; the mother a melancholic seamstress whose father came from Martinique. Boscoe comes first. Prodigiously talented on the piano, he is earning a living by the age of nine, playing classics in the homes of the wealthy. And then comes Geoffrey. He follows his brother around learning to dance and paint and sing like him.

This World Is too Small for this Dream

If you want to know what beauty is, go to Trinidad, where the people have been repeatedly beaten for being too beautiful. Joy is our favourite kind of resistance. The kind where we raise up our skirts and throw back our heads and laugh loud and long, showing off all our teeth. Or dance until the ground is indented with the names of our Gods. Or steal garbage cans on which to play European classics.

Trinidad’s beauty is so unreasonable.

It does not want to be controlled.

It does not want to be less bright, less loud, less blinding.

Trinidad’s beauty is not a good colonial subject. Boscoe and Geoffrey learned the art of that beauty and soon it began to spill out of them. Too much, so soon, too hard not to take notice. It made Trinidad, already a small place, even smaller, too small a place to hold all that talent and range and audacity. An island is a place where you need to know your place. The family remembers the toll of all that brilliance: Boscoe had a nervous breakdown as a teenager; Geoffrey stammered well into his twenties. Speaking out to defend Trinidad in New York is how he found his voice.

Trinidad Is Shango’s Country and Shango Is the God of Dance

The dances they do are the African ones, the bongo and the limbo, in expansive skirts and neckerchiefs, their costumes sewn by their mother. Shango is a dance and the Yoruba God of Dance and of Justice. Shango’s axe is double-headed. It cuts both ways through life’s terrors. To manifest the power of Shango, the dancer lifts a hand to the sky, dragging it back down to Earth in sharp jagged movements that mimic the lightning striking the Earth. The feet dig down to find the place where the lightning strike has left a thunderstone. Shango’s anger is the storm; fire is his symbol of righteousness. They say here that Shango breaks the legs of dancers who are unworthy. Shango, they say, is most powerful here. They are dancers with a daily painting practice, seeing blackness in the songs and the music and the dance, and committing those moments to the canvas.

Later, in New York, it is Haitian loas that draw Geoffrey in. His voice echoes Shango’s demands for justice. It is a reunion of energies. Haiti reminds him that the unconquered ones are always those who see God in their own image and likeness.

A Different Kind of Cultural Intelligence

Now, put the idea out of your head that one was a painter who danced, and one was a dancer who painted. To compare them, to make them competitors, is to use the coloniser’s yardstick. To put a label on their talents is to deny the freedom they were always making in their songs, in their dances, in their paintings. They did not leave to become other people. They did not leave and assimilate and grow into shadows of their former island selves. Leaving gave them space to spread out their hummingbird wings and beat faster and louder, so the small island could be as big as the whole world. They were not the same. They were so different in their sameness. Both leave to pursue dance. Both maintain a daily art practice. Both mined the audacious beauty they had seen in Trinidad to perform with great success to the kind of audiences that any great artist would dream about.

Consider London as the older, more conservative brother of the larger-than-life, chatty New York City. They were so different in their sameness. They both suffered the frustration of people not knowing what else they did.

Looking for Boscoe is a treasure hunt to find his thoughts or his voice when he is not singing. Those who knew him when he came back to Trinidad say he only talked to you if he felt safe to share. And when he did, it was hilarious and provocative in the most tragically serious way that only this island could make you. ‘Introvert’ feels too dread of a word to say that Boscoe preferred to let his art do all the talking. And Geoffrey is everywhere talking, laughing, the little brother, always reminding the world that Boscoe made him want to be great.

Nobody Uses Vetiver Anymore

In Trinidad, vetiver is planted because the roots grow deep enough to hold the hills where the trees have been removed for houses. It is a fire deterrent, and the roots are also turned into bundles of potpourri so that drawers and cabinets have a woody, citrusy smell. It is a useless-looking weed, but nothing is really useless here: the grass roots hold the soil around the houses when the rains come. There is a story told of when Boscoe has died and Geoffrey returns to Trinidad for the last time to lay his brother to rest. And Geoffrey, now wheelchair-bound, sits and waits. No one knows how to welcome him home. The airport staff are unbothered by his presence. This man for whom the mere act of walking through Soho was an experience, sat and waited. And the other travellers began to complain, recognising that greatness is sitting there, forgotten. The world is small again. Small and lonely, and Boscoe is not there to clear a path for him. It is as if all the vetiver has been pulled out of the mountainsides leaving them to slowly dissolve. And what is worse is the roots have been discarded: no one has made those roots into handfuls of potpourri to give that woody, citrusy smell to their cabinets. How We See Us I do not know what other people see when they see the Holder Brothers’ paintings. For me, from the small island with the world shoved into all its corners, I see a Carnival Tuesday afternoon when there is a lull in the endless procession and it is quiet for a moment, except for a steel band in the distance. Before the flag-bearing woman bends the corner to announce who is coming, and you are consumed once again by the heat of a thousand bodies and the noise of their joy, there is a reverent silence. And there, walking towards you, is a man carrying what is left of his costume. He is tired but pleased at his portrayal and, as he adjusts the weight of the headpiece, the fading sunlight paints his shoulders golden. He smiles as he passes, and then the steel band bends the corner, and he quickens his steps to get out of their way. I know him without a word being exchanged. We do not have to explain ourselves to each other. This is what the Holder Brothers mean to me: a secret knowing that you can only learn here. I know the people they paint; I have seen them being present and beautiful every day. I know them. They are me. In the way their skin shines, in the way their eyes smile, in the unsaid words playing on their mouths, in the way their limbs yield and stretch towards the light.

Published by Victoria Miro on the occasion of the exhibitions Boscoe Holder | Geoffrey Holder

1 June

—

27 July 2024

Victoria Miro, 16 Wharf Road,

London N1 7RW

Text © Attillah Springer

Victoria Miro